Learning Zone - Finding Paternity Cases in Sheriff Court Records

How many cases were there? How likely is it that my ancestor's case will be there?

Quick facts

Decree

A decree (or decreet) is a decision made by a court. For the paternity cases we are indexing a decree will be particularly concerned with details of the amount of aliment to be paid, and who would be responsible for paying (usually the father of the child). The decree was legally binding, and if payment was not forthcoming further action could be taken to enforce the decree. A decree will usually clearly identify all the individuals concerned, giving their addresses, if they were known. Former addresses are common. Relatives of both parties are also frequently named. The date of birth and sex of the child is almost always given (but not normally the forename).

Extracted Decree

If an official written copy of the decision of the court was required (usually for enforcement) an extract of the decree would be made. When this happened, from about 1830 onwards (and sometimes earlier) a copy would also be entered in what was called the 'Register of Extracted Decrees'. If a copy or extract was not requested then the decree would not be entered in this register (even if the court had made a decree).

Unextracted Decree

When no extract was made, the text of the decree may still exist. Prior to 1860 decrees can usually be found in the processes (or case papers) relating to the action. These court processes can also tell us more about cases even where an extract was made and can be found in the Register of Extracted Decrees.

Processes

The 'processes' are the bundles of paperwork relating to the case. Processes usually include the final decree (unless a case did not reach decree) and can also tell us more about cases even where an extract was made and can be found in the Register of Extracted Decrees. The paperwork of each case varies. After 1860 the processes have been largely destroyed, which is a great shame from our point of view. Before 1860, though, most of the processes survive and these can prove fascinating; they have even been known to include love letters!

What, why, where?

One resource in Scotland which can help in this situation is the Sheriff Court records, most of which are held by the National Records of Scotland. In particular we are referring to civil court actions heard by the Sheriff Courts entitled 'Actions of Affiliation and Aliment'. We often speak of these as paternity cases, although they are not normally referred that way in the records.

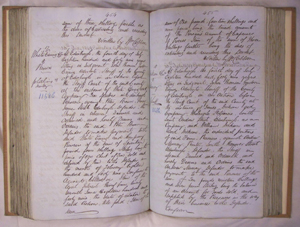

In most of these cases, you will find details of an attempt to compel a father to give financial support for an illegitimate child. We are grateful to the National Records of Scotland who have given us permission to show examples from these records here. Click on the images below to enlarge them (Sheriff Court Decree: NRS reference SC39/8/26).

Evidence would be presented, perhaps an acknowledgement from the father, or the testimony of witnesses, in order to establish the individual responsible for the maintenance of the child.

The records of these cases are particularly useful because as the 19th century progressed, the grip that the church once had on people’s lives was waning, especially in urban areas. Also, whilst the Sheriff Court material largely survives, records of many churches have been lost. This means that while church records, such as the Kirk Session minutes of Presbyterian churches, can be very useful in cases of illegitimacy, it may be that you need to turn to the Sheriff Court records.

How many cases were there? How likely is it that my ancestor’s case will be there?

These are big questions, and we do not yet know all the answers. Just to give an indication, though, we have taken a sample year from the mid-19th century to see if we can get even a rough idea. We took five counties in southern Scotland for the year 1858. For that year, we have calculated that just under 15% of illegitimate births had some kind of record in the Sheriff Court, around 10% of which included extracted decrees.

Where to start!

Where possible we would recommend starting with the volumes of extracted decrees. The books sometimes have an index at the back (or occasionally at the front) so always look for this before you start browsing through the volume. Remember, though, that these indexes are generally arranged alphabetically by the pursuer’s surname (usually this is the mother).

These volumes commence in most courts around 1830, likely as a result of the restructuring of the Scottish courts that was taking place at that time. Most Sheriff Courts have complete runs of these volumes into the 20th century, although sadly Aberdeen is an exception to this. To determine if they do exist for the area you are searching in, you will need to use the National Records of Scotland (NRS) catalogue, which is available online. For more information on how to use the NRS catalogue, you can download our PDF guide 'Tracing Your Illegitimate Ancestors in the Sheriff Court Records'.

Digging Deeper

The paperwork of each case varies. After 1860 the processes have been largely destroyed, which is a great shame from our point of view. Before 1860, though, most of the processes survive and these can prove fascinating. A typical box of Sheriff Court Processes is shown below (NRS reference: SC62/10/390).

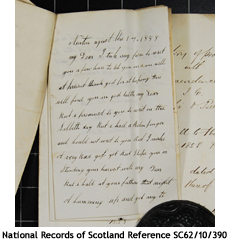

Sometimes a father would quickly accept responsibility for the child, and in such cases the processes tend to be less extensive. In other cases, though, the testimony of witnesses would be presented, including statements of when and where the couple were seen. The woman could recount occasions when she met the child’s father and mention who had seen them walking out together. If you’re really fortunate the pursuer will have produced her love letters as evidence and they will be preserved down to this day.

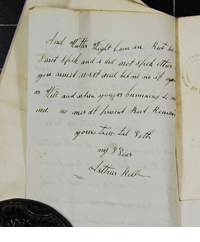

The images above (click to enlarge) are from a case found in the National Records of Scotland and referenced SC62/10/390. Here is a transcription with corrected spelling) of the letter shown above:

“Newton August the 17, 1858

My Dear I take my pen to write you a few lines to let you know I am well at present - thank God for it. Hoping this will find you in good health my dear but I promised to you

to write on the Sabbath day But I had a belen finger and could not write to you But I make a very bad job yet But I hope you are standing your harvest well my dear But I called

at your father that night A coming up and got my tea and Walter Wight came in But he did not speak and I did not speak either. But you must write and let me know if you are well

and when you are coming to meet me. No more at present, But remains yours true till death my dear. Arthur Bell”

This goes to demonstrate how much these records can really help you understand your ancestors, as well as trace your genealogy. To download a copy of this example case, please click here. Please note that it is a large file so the download may take a while. The images are supplied for your personal reference and may not be reproduced without our consent and that of the National Records of Scotland. If you do wish to share them with other people please either direct them to our website or get in touch and we’ll see what we can arrange.

Our Indexing Project

So far the Registers of Extracted Decrees for the Sheriff Courts of almost all the counties of Scotland have been completely indexed. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to keep up-to-date with the most recent releases.

Frequently Asked Questions

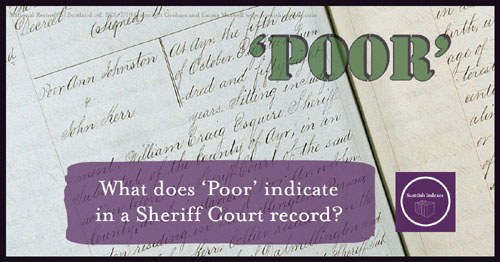

What does 'Poor' indicate in a Sheriff Court record?

It is not unusual to see 'Poor' next to the pursuer's name in an affiliation and aliment case and you may have wondered what this means. These are cases where the mother of an illegitimate child takes the father to court to prove he is the father of the child and compel him to pay towards the child’s care.

In general, many of these women were young, unmarried and therefore not wealthy. Many of these women could not afford to take the father of their baby to court.

The Scottish courts had a provision for those who through poverty could not pursue or defend a case. It was called the 'poor's roll, which was not the same thing as the poor relief roll of the parish, but rather a provision made at the courts. It was enacted that there had to be legal agents available at each court to represent the poor and these would be obliged to give their services free of charge, as well as court fees being waived if a person was deemed to qualify. To qualify for the poor's roll of the court, a person would have to give evidence of their poverty, and a certificate from the local minister in a prescribed format was the most common way of doing this. The Sheriff would then decide if the person could be added to the 'poor's roll' of the court. If it was determined they qualified, their name would be preceded by the word 'Poor' in the subsequent court paperwork.

Of course, if the pursuer was successful, the defender would be liable for expenses in any case.

Therefore, if you see 'Poor' next to the name of your ancestor in a Sheriff Court aliment case it means that she was given assistance directly by the court.